Displaying items by tag: Monitoring

Kiwi call monitoring at Tawharanui

In New Zealand we have our special icon, the Kiwi. This is the only country in the world where Kiwi live. They make their burrows in the undergrowth and enjoy running about searching for worms and spiders.

However, with such a lot of predators now, it is wise to have Kiwi either in a safely fenced or pest monitored area. At Tawharanui we have just that right situation, with the Predator Proof Fence across the Tokatu Point at the termination of Tawharanui Peninsular, giving freedom to all native creatures within.

Kiwi breed around Autumn each year, once they are old enough. This is about two years old. They like to call at twilight which is the two hours after the sun goes down. So Kiwi Call Monitoring occurs when volunteers sit during those two hours usually 6 – 8pm, in June each year, silently listening for the calls.

Once the first call is heard then a count is commenced, slowly, sometimes reaching to over 20 times. These are usually the male birds with their shrill high whistles. Then occasionally a female will call with her lower guttural tones. Sometimes, all is then quiet. Perhaps they have found their mate!

Once the two hours is completed the volunteers collect together again at their base for supper and a chat about their evening event.

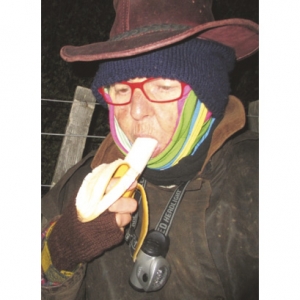

Sitting out in the dark at this time can be very cold in New Zealand. So good warm woolly and dry clothing is essential. Usually dry nights with little wind are chosen. The moon is rarely visible. Try it sometime – it’s a thrilling experience!

Patti Williams

Operation Duck Pond

With about 90 percent of New Zealand’s wetland lost over the past 150 years, Fish & Game NZ realises there’s a compelling need to assess the role that ponds play in successfully managing waterfowl.

Ponds have been established across the New Zealand landscape for various purposes including stock watering, irrigation, storm water capture, effluent ponding, waterfowl habitat and simple aesthetic values. Currently, there’s little scientific information on what, and how big a role these ponds play as habitat for waterfowl populations.

The aim of this ‘citizen science’ project is to determine what pond habitat features provide good breeding for waterfowl, and promote good pond management practices for breeding these birds. Fish & Game has launched an appeal for people who want to monitor waterfowl populations on ponds around their area. The aim is to establish a network of ponds to be closely monitored over the breeding season.

You don’t have to be a scientist! All volunteers will be given a set of simple instructions on how to go about monitoring. Fish & Game will supply a manual with simple instructions on how to run their surveys – so everyone round the country is tackling the project the same way, and volunteers gather the best data possible.

If you’re keen to help with collection of data and are prepared to monitor a pond, a fun and fulfilling project that will help New Zealand’s waterfowl and other native water dependant birds, this project is for you. Don’t forget – we are keen to hear from a wide range of people, including youngsters. Kids – depending on your age, you may need to line up support from mum and dad, a friend or relation.

Your help in this project will not only provide data to drive management decisions, but will give waterfowl enthusiasts, hunters and landowners a unique opportunity to get involved and make a real hands on contribution to our efforts to manage waterfowl – and keep their numbers up!

DU director takes up DOC role

DU director and bittern expert Emma Williams’ workload has become a whole lot busier after she was appointed science advisor (wetland birds) for the Department of Conservation in October.

A fulltime job for four years, her main task is to deliver the national bittern research plan. The role also involves work with other wetland birds such as spotless crakes and marsh crakes with the aim of setting up new collaborations with organisations to try to fill some of the knowledge gaps about cryptic and native wetland birds.

Projects include working with Stephen Hartley and students at Victoria University in Wairarapa Moana. One of the current projects involves putting out artificial bittern nests in several study sites, including Wairio, to determine what predators are targeting bitterns.

Emma says new bittern monitoring projects in South Kaipara, Auckland region, Tauranga and Turangi are expanding DOC’s national monitoring reach. The goal is to identify where bittern strongholds and hot spots are and inform where new projects are needed to try to reverse bittern declines.

Hunt for the puweto

Starling and Myna birds caught interfering with duck nesting

The myna also frequently pulled nesting material from below over the teal eggs to try to bury them so it could take over the box for itself. Once the teal began sitting on the eggs full-time to incubate them, the myna gave up and the teal eventually successfully hatched the whole clutch. Game cameras have invisible infra-red capability and this can tell us what is happening at any hour of the day or night at times and places we could previously only speculate about.

This same problem also exists in the US where wood duck nest box complexes can get taken over by introduced starlings. Researchers have tried all manner of deterrents including mirrors inside the nest boxes and even flashing lights. Neither seems to dissuade the starlings from displacing the wood ducks. Starlings cover up duck eggs with fine grass and similar material. However starlings like to nest in a dark corner of the box. Cutting a 100x100mm hole in the lid and adding a diffuser skylight that transmits 80-89% of light thwarted this desire by lighting up the nest box corners too. The wood ducks however don’t seem to mind this new accessory. This is now being trialled in NZ to see if myna birds are similarly deterred and grey teal not.

When starlings adopt a wood duck nest box, they intimidate and even attack the resident wood duck trying to get back in. Another successful ruse used to defeat the starlings is to use their own biology to best advantage.

This has also been trialled in NZ with native grey teal and our own introduced starlings. Lacking a proper study it might be premature to call it a success, but starlings have certainly used the smaller starling boxes and when they do they have not been found inside the larger teal box. However on one occasion the two species shared the same plain nest box and, a bit like cats trying to avoid fight perhaps, they each looked and faced the other way as they incubated side by side, the starling in the corner, the teal in the middle.

Roof cam

The “roof cam” inside the afore mentioned teal box took no less than 7,587 photos of a wriggly restless grey teal which suggests that the myna bird may have left more than just rubbish. Both mynas and starlings are host to bird mites. As many as 5000 of these can infest a nest box and come out at night to suck the birds blood. Pulling back the nesting material will reveal a grey mass of eggs in corners and the mites themselves will live in creaks in the structure.

The latter can be avoided at box building time by putting PVA glue in all the joints. About $30 worth of quaternary ammonia will make up 32-litres and this actually dissolves the mites if any are present. So this might be a useful thing to do when servicing nest boxes, (they need old nesting material removed and new added each year. (This also, incidentally, stops parasite build up in the nest).

Sounds like a great MSc study to me as grey teal do not readily desert nests so obtaining data should be straight forward. When grey teal nest boxes are serviced each year in March/April, the sheer amount of rubbish left in them by mynas and to a lessor extent starlings is hard to credit and often more than one clutch of grey teal eggs lies buried somewhere in the middle.

So sorting out starling and myna problems can potentially make grey teal nest box complexes even more productive than currently.

A new article on best practice for grey teal nest box construction and maintenance has recently been added to the NZ Fish & Game website.

By John Dyer,

Auckland/Waikato Fish & Game Council